Splang: A Playlist Defined Esolang

Creating an esolang from scratch for CS198-134

Abstract

splang is a music-inspired, Turing-complete esolang that blends artistic expression with computational logic. splang is inspired by the personal significance or emotions a playlist can elecit, as way to express oneself, interact with others, or share experiences. With this in mind, splang aims to be both playful and expressive, encouraging programmers to compose their logic with the same intention and nuance that goes into crafting the perfect playlist. A language that seamlessly enables artistic expression in a functional language.

splang is designed to work with Spotify, a music streaming service and application developed by Spotify Technology S.A. Their feature-rich IDE enables users to create, edit, share, and collaborate on splang programs through their playlist interface, all while listening to music! A public method to execute splang programs is in development, but in the interim, users can run their programs through the Splang interpreter written in Python. Just pip install splang and run splang -hello to run your first splang.

Language Design

A large source of my inspiration for this project came from Piet, a language that uses images as code. In a similar vein, I wanted to create a language that uses music as code, specifically allowing users to create a playlist as a program. While an initial search of music based esolangs showed impressive languages such as PianoFuck by Sam Poder, I only encountered one which operated with Spotify, Slang, a esolang using Spotify songs to replace BF’s 8 commands. This language demonstrated the potential of using music and playlists as a programming language, but ultimately the language was an extension of BF, and I wanted to create a language that was more expressive, flexible, and took advantage of the choice of songs in a playlist rather than just using genres as commands. I would additionally like to thank Siddhant Vasudevan for his inspiration in the idea of using music as code.

Additionally, I wanted to experience the process of creating a language from scratch, and the challenges that come with it. Instead of using a pre-existing language as a base, and simply implementing a transpiler, I wanted to create a language that was unique and had its own set of commands, syntax, and semantics. This would allow me to explore the design choices that go into creating a language, and the trade-offs that come with those choices.

Because Splang is a language that uses playlists as code, each song in the playlist will represent a command, and the order of the songs determines the flow of the program.

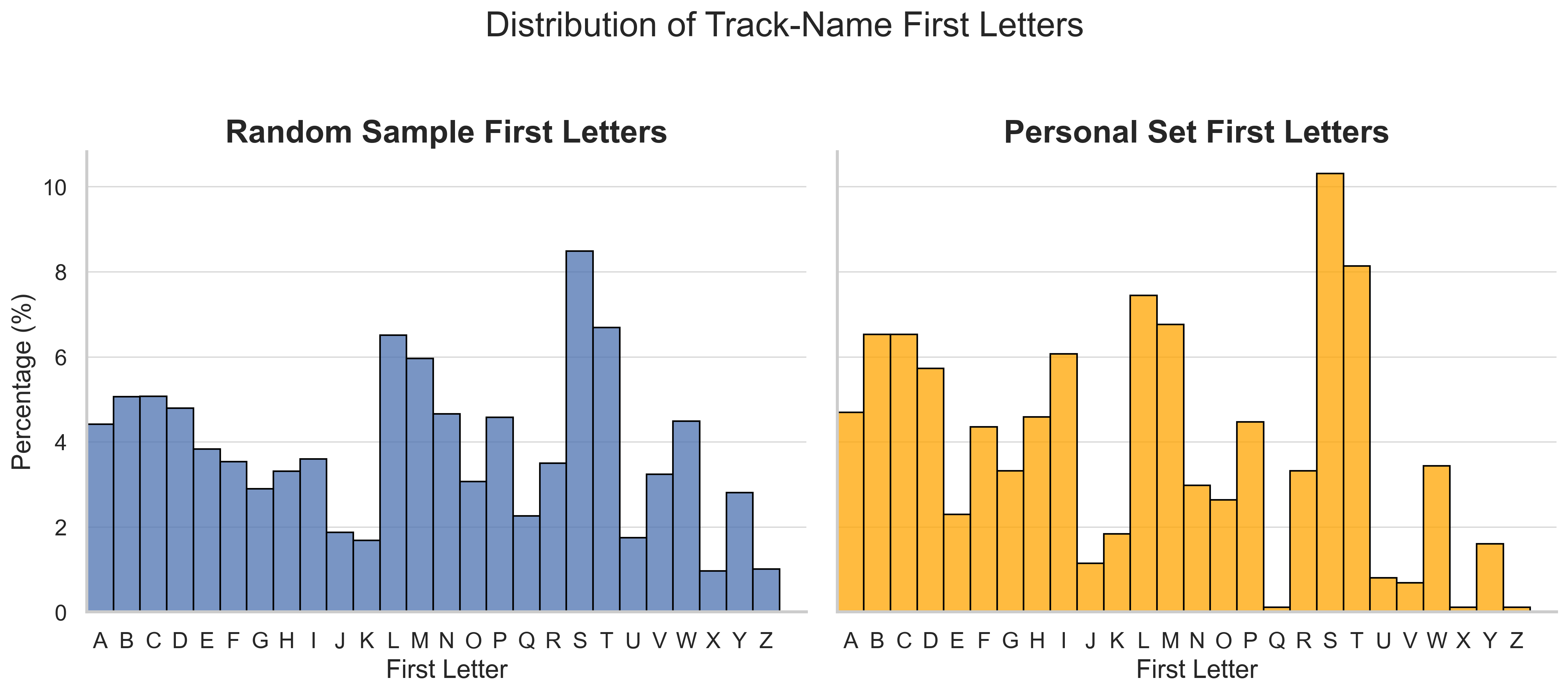

The first question that came to mind was how to represent the commands, there are many attributes of a song that could be used, such as the title, artist, album, genre, and duration. To create a usable language, I needed to choose a set of attributes that would be easy to use, allow for the creation of a enjoyable playlist, and had a good distribution of songs. This ruled out using the title, artist, and album as commands, as there are too many unique songs, and even using factors such as the first letter would have an unequal distribution of songs.

As we can see from the chart above, the first letter of a song’s title is not evenly distributed, with a large number of songs starting with the letter “S” and barely any in my library with the letter “Q”, “X”, or “Z”. My goal was to ensure the programmer had a good selection of songs to choose from, and didn’t necessarily have to spend a long time searching for songs, so the first letter of any alphabetical attribute was not a good choice.

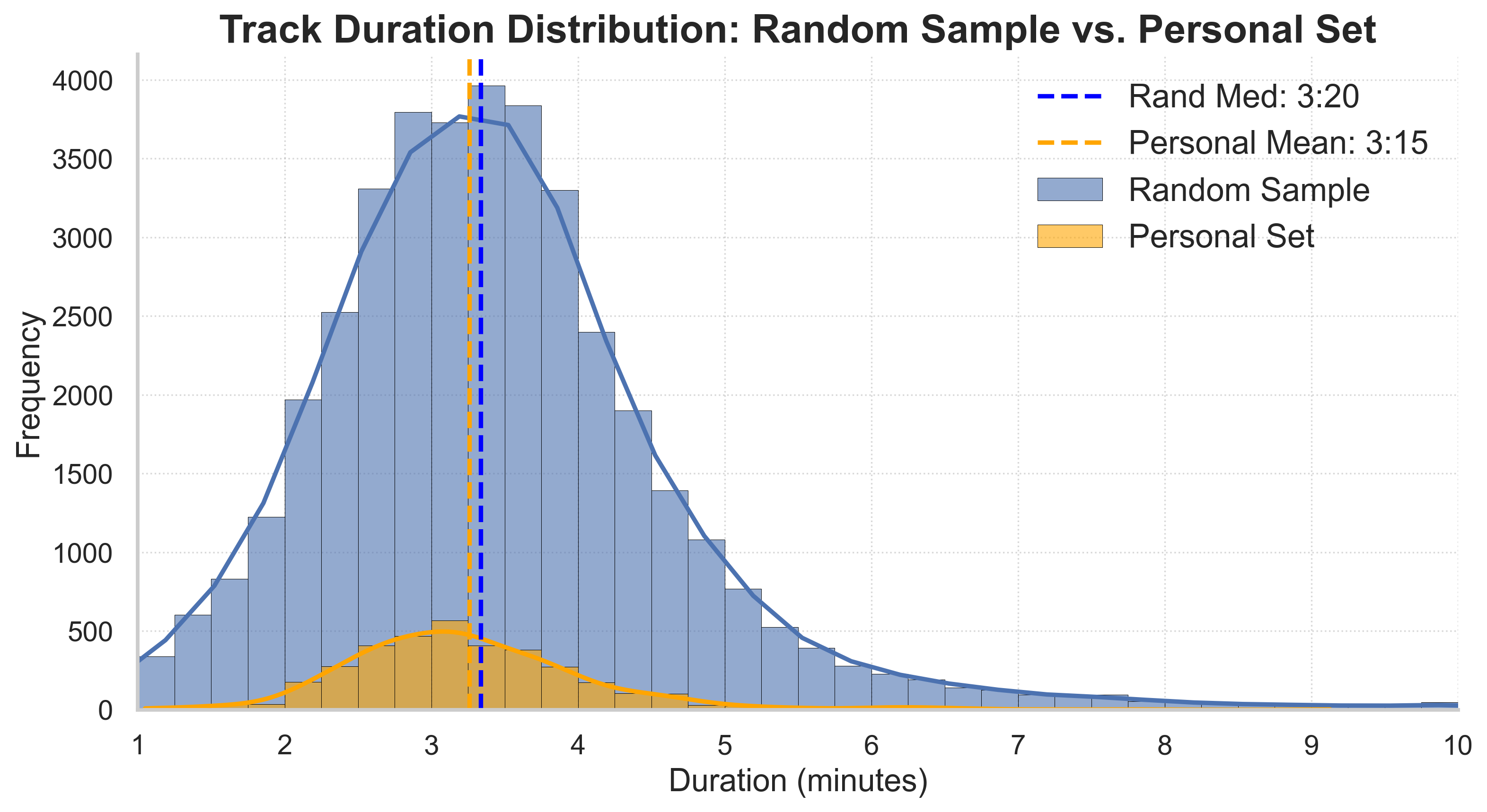

I also ruled out using the genre, as we should be able to create a coherent playlist without having to constantly switch genres. In terms of data visible to the programmer, the only attribute left was the duration of the song. This attribute is visible to the programmer formatted as mm:ss in the IDE, but is visible in the API as milliseconds. As such, we will have to convert the duration in milliseconds to the visible seconds format, rounding our values to the nearest second and converting times such as 1:60 to 2:00. After extensive testing, I was able to reverse engineer the conversion from milliseconds to seconds, as done in the IDE, to have the correct seconds value.

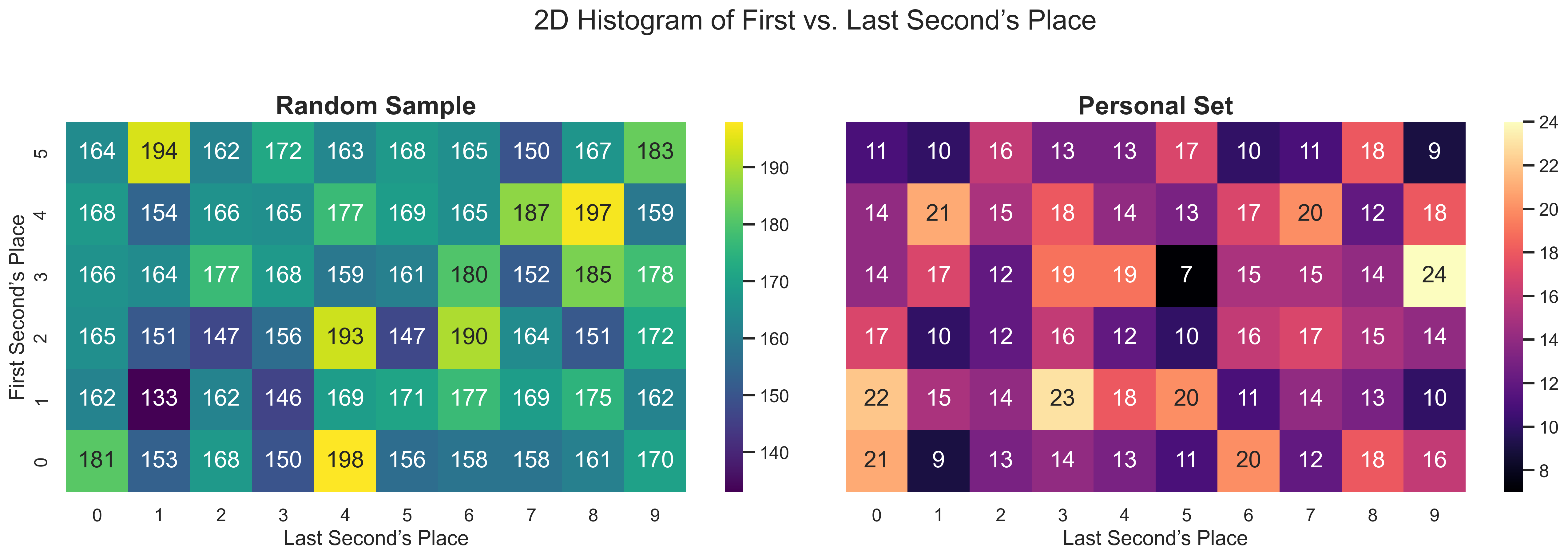

In the same way, we need to ensure that the distribution of these seconds values is even, so I tested my own personal library of songs and 10,000 randomly sampled songs from Spotify. The results were promising, with a good distribution of songs across the seconds values.

As we can see from the charts above, the distribution of seconds values is relatively even, with no statistically significant outliers.

The next step was to determine what kind of language I wanted to create. While a BF extension was a possibility, it had already been done, and even if I could have improved upon it, I had much more than 8 command possibilities. I wanted my language to have built in data structures, such as a stack and heap, and to be able to use the playlist to interact with the data structures. I also wanted to have loops, conditionals, ways to interact with stdin/stdout, labels, jumps, NOPs, and halts. I started my thoughts with the concepts from Whitespace, having certain sequences being treated as IMP sequences, and following songs acting as parameters, and further built upon that with ideas gained from my knowledge of the RISC-V instruction set.

Splang will not recieve an update until a time comes that a consensus within the community is reached on the functionality of the remaining commands, however in their current state, they are left to the end user as an opportunity for custom implementations.

As such, I present the Splang v1.0 Language Reference.

Splang v1.0 Language Reference

| Keyterm | Description |

|---|---|

| LS | Last Second’s place, e.g 3:45 –> 5 |

| FS | First Second’s place , e.g 3:45 –> 4 |

| TrackID | The unique ID of a song in Spotify’s database. |

| (song + n) | The song n positions after the current song in the playlist. |

| Stack | A LIFO data structure, operates on single elements. |

| Heap | A data structure that stores values at a specific index, operates on single elements. |

| RA Stack | A LIFO data structure that stores return addresses for function calls. |

| Time | Command | Parameter(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0:00 | NOP | None | No operation, does nothing. |

| 0:01 | HALT | None | Halts the program. |

| 0:02 | LABEL | 1 | Label, defines the (song + 1)’s trackID as a label. |

| 0:03 | JUMP | 1 | Jumps to the label defined by the (song + 1) trackID. |

| 0:04 | JUMPZ | 1 | Jumps to the label defined by the (song + 1) trackID if the top of the stack is 0. |

| 0:05 | JUMPNZ | 1 | Jumps to the label defined by the (song + 1) trackID if the top of the stack is not 0. |

| 0:06 | JUMPZ_HEAP | 1 | Jumps to the label defined by the (song + 1) trackID if the value at the index defined by the (song + 1) trackID in heap is 0. |

| 0:07 | JUMPNZ_HEAP | 1 | Jumps to the label defined by the (song + 1) trackID if the value at the index defined by the (song + 1) trackID in heap is not 0. |

| 0:08 | CALL | 1 | Pushes return address to RA stack and jumps to the label defined by the (song + 1) trackID. |

| 0:09 | RETURN | None | Pops the return address from the RA stack and jumps to it. |

| 0:10 | ADD | None | Adds the top two elements of the stack and pushes the result. |

| 0:11 | SUB | None | Subtracts the top two elements of the stack and pushes the result. |

| 0:12 | MUL | None | Multiplies the top two elements of the stack and pushes the result. |

| 0:13 | DIV | None | Divides the top two elements of the stack and pushes the result. |

| 0:14 | MOD | None | Modulus of the top two elements of the stack (b mod a) and pushes the result. |

| 0:15 | POW | None | Raises the top element of the stack to the power of the second top element and pushes the result. |

| 0:16 | Not_implemented | None | Not implemented. |

| 0:17 | Not_implemented | None | Not implemented. |

| 0:18 | Not_implemented | None | Not implemented. |

| 0:19 | Not_implemented | None | Not implemented. |

| 0:20 | PUSH_LS | 1 | Pushes the LS of the (song + 1) duration to the stack. |

| 0:21 | PUSH_FS | 1 | Pushes the FS of the (song + 1) duration to the stack. |

| 0:22 | SHIFT_R_LS | 1 | Shifts the value of the top element of the stack to the right, adding the LS of the (song + 1)’s duration. |

| 0:23 | SHIFT_L_LS | 1 | Shifts the value of the top element of the stack to the left, adding the LS of the (song + 1)’s duration. |

| 0:24 | SHIFT_R_FS | 1 | Shifts the value of the top element of the stack to the right, adding the FS of the (song + 1)’s duration. |

| 0:25 | SHIFT_L_FS | 1 | Shifts the value of the top element of the stack to the left, adding the FS of the (song + 1)’s duration. |

| 0:26 | POP | None | Pops the top element of the stack. |

| 0:27 | DUP | None | Duplicates the top element of the stack. |

| 0:28 | SWAP | None | Swaps the top two elements of the stack. |

| 0:29 | Not_implemented | None | Not implemented. |

| 0:30 | STORE | 1 | Stores the top element of the stack in heap at the index defined by the (song + 1)’s trackID. |

| 0:31 | STORE_TOP | None | Stores the top element of the stack in the heap at the index defined by the second element of the stack. |

| 0:32 | LOAD | 1 | Loads the value at the index defined by the (song + 1)’s trackID from heap to the stack. |

| 0:33 | LOAD_TOP | None | Loads the value at the index defined by the top element of the stack from heap to the stack. |

| 0:34 | INC_HEAP | 1 | Increments the value at the index defined by the (song + 1)’s trackID in heap. |

| 0:35 | DEC_HEAP | 1 | Decrements the value at the index defined by the (song + 1)’s trackID in heap. |

| 0:36 | INC | None | Increments the top element of the stack. |

| 0:37 | DEC | None | Decrements the top element of the stack. |

| 0:38 | Not_implemented | None | Not implemented. |

| 0:39 | Not_implemented | None | Not implemented. |

| 0:40 | STDIN_INT | None | Reads an integer until a newline from stdin and pushes it to the stack. |

| 0:41 | STDIN | None | Reads a string until a newline from stdin and pushes each character to the stack as an ASCII value. |

| 0:42 | STDOUT_INT | None | Pops the top element of the stack and prints it to stdout as an integer. |

| 0:43 | STDOUT | None | Pops the top element of the stack and prints it to stdout as an ASCII character. |

| 0:44 | READ_CHAR | 1 | Reads the first character of the (song + 1)’s title and pushes it to the stack as an ASCII value. |

| 0:45 | LISTEN | 1 | Sleeps for the full duration of the (song + 1). |

| 0:46 | Not_implemented | None | Not implemented. |

| 0:47 | Not_implemented | None | Not implemented. |

| 0:48 | Not_implemented | None | Not implemented. |

| 0:49 | Not_implemented | None | Not implemented. |

| 0:50 | AND | None | Logical AND of the top two elements of the stack and pushes the result. |

| 0:51 | OR | None | Logical OR of the top two elements of the stack and pushes the result. |

| 0:52 | XOR | None | Logical XOR of the top two elements of the stack and pushes the result. |

| 0:53 | NOT | None | Logical NOT of the top element of the stack and pushes the result. |

| 0:54 | EQUAL | None | Checks if the top two elements of the stack are equal and pushes the result. |

| 0:55 | NOT_EQUAL | None | Checks if the top two elements of the stack are not equal and pushes the result. |

| 0:56 | GREATER | None | Checks if the top element of the stack is greater than the second top element and pushes the result. |

| 0:57 | LESS | None | Checks if the top element of the stack is less than the second top element and pushes the result. |

| 0:58 | GREATER_EQUAL | None | Checks if the top element of the stack is greater than or equal to the second top element and pushes the result. |

| 0:59 | LESS_EQUAL | None | Checks if the top element of the stack is less than or equal to the second top element and pushes the result. |

Issues

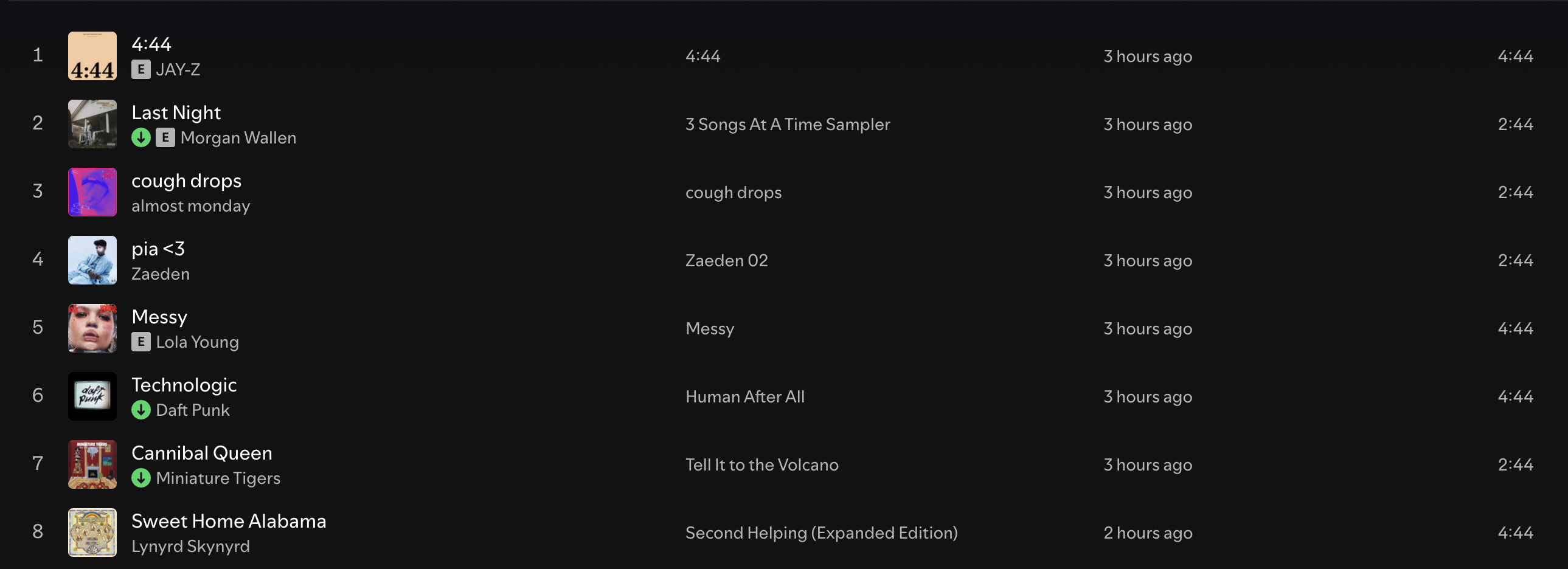

There is inconsistent conversion from duration_ms to displayed duration in the Spotify UI. For example, Sweet Home Alabama by Lynyrd Skynyrd is displayed as 4:43, but the duration_ms is 283800. When playing the song, it may initially flash 4:44 in the playback bar UI, but will then change to 4:43. Different times are displayed on the WebUI vs the CEF application. While timings were completely unpredictable in the WebUI, the CEF application was consistent with most songs, 89 of my randomly sampled songs successfully converted to the correct seconds value, however Sweet Home Alabama never achieved the 4:43 seconds value without ruining the conversion for other songs.

The only consistent way to get the correct seconds value is to use the CEF application’s displayed seconds value once added to your playlist. Search results on the CEF application may occasionally display the correct seconds value, but this is not guaranteed.

My conclusion is that splang’s IDE is still in ongoing development by the Spotify team!

Examples

Hello World

Here is Hello World in Splang, a simple program that prints “HELLOWORLD” to the screen. The program is defined as a playlist, and each song in the playlist represents a command in the language. The program is designed to be edited in the IDE, and run through the Splang interpreter.

This splang interacts with the stdout, as well as the heap and stack. It takes advantage of loops, jumps, and labels to print HELLOWORLD. Shareable through the link https://open.spotify.com/playlist/7cPsICy0U7WM8Q67SuYXds, which could be compressed to 7cPsICy0U7WM8Q67SuYXds, the only part of the URL that is needed to run the program, Splang is clearly a very efficient language and has the incredible property of all programs taking the same amount of local storage, 22 bytes! We will have to thank the IDE developers for providing this service along with our subscription!

Here’s a step-by-step walkthrough of how this playlist program prints HELLOWORLD:

-

PC 0 –

duration_min = 4:44⇒ seconds = 44 ⇒READ_CHAR(1 param)- Param at PC 1:

first_letter = 'D'⇒ pushord('D') = 68onto the stack - Advance PC: 0 + 1 + 1 = 2

- Param at PC 1:

-

PC 2 –

4:44⇒READ_CHAR- Param at PC 3:

'L'⇒ push 76 - Next PC: 4

- Param at PC 3:

-

PC 4 –

4:44⇒READ_CHAR- Param at PC 5:

'R'⇒ push 82 - Next PC: 6

- Param at PC 5:

-

PC 6 –

2:44⇒READ_CHAR- Param at PC 7:

'O'⇒ push 79 - Next PC: 8

- Param at PC 7:

-

PC 8 –

2:44⇒READ_CHAR- Param at PC 9:

'W'⇒ push 87 - Next PC: 10

- Param at PC 9:

-

PC 10 –

4:44⇒READ_CHAR- Param at PC 11:

'O'⇒ push 79 - Next PC: 12

- Param at PC 11:

-

PC 12 –

2:44⇒READ_CHAR- Param at PC 13:

'L'⇒ push 76 - Next PC: 14

- Param at PC 13:

-

PC 14 –

2:44⇒READ_CHAR- Param at PC 15:

'L'⇒ push 76 - Next PC: 16

- Param at PC 15:

-

PC 16 –

3:44⇒READ_CHAR- Param at PC 17:

'E'⇒ push 69 - Next PC: 18

- Param at PC 17:

-

PC 18 –

3:44⇒READ_CHAR- Param at PC 19:

'H'⇒ push 72 - Next PC: 20

- Param at PC 19:

-

PC 20 –

2:20⇒PUSH_LS(1 param)- Param at PC 21: (last_second = 9) ⇒ push 9

- Next PC: 22

-

PC 22 –

2:36⇒INC- Increment top of stack (9) by 1 ⇒ push 10

- Next PC: 23

-

PC 23 –

4:30⇒STORE(1 param)- Param at PC 24:

track_id = 'Think About'⇒ pop 10, storeheap['Think About'] = 10 - Next PC: 25

- Param at PC 24:

-

PC 25 –

4:02⇒LABEL(1 param)- Param at PC 26:

track_id = 'Think About'⇒ recordlabels['Think About'] = 25 + 1 + 1 = 27 - Next PC: 27

- Param at PC 26:

Loop (prints one character per iteration)

Each iteration runs the three instructions below, popping one stack value and decrementing the heap counter until it hits zero.

a. PC 27 – 3:43 ⇒ STDOUT

- Pop top of stack and print it as

chr(...) -

Iterations print, in order:

- 72 ⇒ “H”

- 69 ⇒ “E”

- 76 ⇒ “L”

- 76 ⇒ “L”

- 79 ⇒ “O”

- 87 ⇒ “W”

- 79 ⇒ “O”

- 82 ⇒ “R”

- 76 ⇒ “L”

- 68 ⇒ “D”

b. PC 28 – 3:35 ⇒ DEC_HEAP (1 param)

- Param at PC 29:

track_id = 'Think About'⇒ decrementheap['Think About']by 1

c. PC 30 – 4:07 ⇒ JUMPNZ_HEAP (1 param)

- Param at PC 31:

track_id = 'Think About'⇒ checkheap['Think About'] - If

heap['Think About'] != 0, jump back to PC 27; otherwise fall through - After 10 iterations,

heap['Think About']goes from 10 down to 0, so the loop stops.

-

PC 32 –

3:01⇒HALT- Stop execution

Final printed output:

HELLOWORLD

This splang is quite simple, but it is extendable to inputing any given length string, and printing it to the screen. The only limitation is the length of the string, which is limited by the number of songs in the playlist, usually around 10,000 songs for Spotify. However, through your own custom playlist definition, you can bypass this limitation to run local splangs.

Fibonacci

Here is Fibonacci in Splang, a more complex program that computes the fibonacci sequence and prints the first 406 Fibonacci numbers to the screen.

This splang demonstrates use of loops and function calling, yet additionally demonstrates that recursion is possible with careful stack design, although our computation here is sequential.

🟩 SETUP PHASE

-

PC 0 –

"Push It to the Limit – Bonus"⇒PUSH_LS(1 param)- Param at PC 1:

"1999"⇒last_second = 9⇒ push 9 - Stack :

[9]

- Param at PC 1:

-

PC 2 –

"One More Time"⇒PUSH_LS(1 param)- Param at PC 3:

"90210"⇒last_second = 9⇒ push 9 - Stack :

[9, 9]

- Param at PC 3:

-

PC 4 –

"One More Time"⇒PUSH_LS(1 param)- Param at PC 5:

"1 2 365 4 Me"⇒last_second = 5⇒ push 5 - Stack :

[9, 9, 5]

- Param at PC 5:

-

PC 6 –

"The Times They Are A-Changin'"⇒MUL(no params)- Compute:

5 × 9 = 45 - Stack :

[9, 45]

- Compute:

-

PC 7 –

"The Times They Are A-Changin'"⇒MUL(no params)- Compute:

9 × 45 = 405 - Stack :

[405]

- Compute:

-

PC 8 –

"Store"⇒STORE(1 param)- Param at PC 9:

"Variable"⇒ pop 405, storeheap["Variable"] = 405 - Stack :

[] - Heap :

{ "Variable": 405 }

- Param at PC 9:

🟨 SEED INITIAL FIBONACCI TERMS

-

PC 10 –

"Pump Up The Jam"⇒PUSH_LS(1 param)- Param at PC 11:

"Zero To Hero"⇒last_second = 0⇒ push 0 - Stack :

[0] - Heap :

{ "Variable": 405 }

- Param at PC 11:

-

PC 12 –

"Push It"⇒PUSH_FS(1 param)- Param at PC 13:

"One Thing"⇒first_second = 1⇒ push 1 - Stack :

[0, 1] - Heap :

{ "Variable": 405 }

- Param at PC 13:

🏷️ LOOP AND FIB CALL

-

PC 14 –

"Label"⇒LABEL(1 param)- Param at PC 15:

"Variable"⇒ define label"Variable"at PC 16 - Stack :

[0, 1] - Heap :

{ "Variable": 405 }

- Param at PC 15:

-

PC 16 –

"Call You"⇒CALL(1 param)- Param at PC 17:

"Fibonacci (Part 1)"⇒ jump to FIB function - Stack :

[0, 1] - RA Stack :

[18] - Heap :

{ "Variable": 405 }

- Param at PC 17:

-

PC 18 –

"Godzilla-1.0 Elegy"⇒DEC_HEAP(1 param)- Param at PC 19:

"Variable"⇒heap["Variable"] -= 1⇒ now 404 - Stack :

[1, 1] - Heap :

{ "Variable": 404 }

- Param at PC 19:

-

PC 20 –

"Jumpin Jumpin"⇒JUMPNZ_HEAP(1 param)- Param at PC 21:

"Variable"⇒ jump to label"Variable"(PC 14) if heap ≠ 0 - Stack :

[1, 1] - Heap :

{ "Variable": 404 }

- Param at PC 21:

🟥 PROGRAM EXIT

-

PC 22 –

"Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us Now"⇒HALT(no params)- Executed only when

heap["Variable"] == 0 - Stack : \([x_n, x_{n+1}]\)

- Heap :

{ "Variable": 0 }

- Executed only when

🔁 FIB FUNCTION

-

PC 23 –

"Label"⇒LABEL(1 param)- Param at PC 24:

"Fibonacci (Part 1)"⇒ define label"Fibonacci (Part 1)"at PC 25 - Stack : \([x_n, x_{n+1}]\)

- Heap : \(\{\text{Variable}: n\}\)

- Param at PC 24:

-

PC 25 –

"Duplicates"⇒DUP(no params)- Duplicate top of stack: \(x_{n+1}\)

- Stack : \([x_n, x_{n+1}, x_{n+1}]\)

-

PC 26 –

"Store"⇒STORE_TOP(1 param)- Param at PC 27:

"Old Recliners"⇒ pop \(x_{n+1}\), store inheap["Old Recliners"] =\(x_{n+1}\) - Stack : \([x_n, x_{n+1}]\)

- Heap : \(\{\text{Variable: } n, \text{Old Recliners: } x_{n+1}\}\)

- Param at PC 27:

-

PC 28 –

"Wasted Summers"⇒ADD(no params)- Compute: \(x_n + x_{n+1} = x_{n+2}\)

- Stack : \([x_{n+2}]\)

-

PC 29 –

"Duplicates"⇒DUP(no params)- Duplicate top of stack: \(x_{n+2}\)

- Stack : \([x_{n+2}, x_{n+2}]\)

-

PC 30 –

"Say It Like You Mean It"⇒STDOUT_INT(no params)- Print \(x_{n+2}\) as an integer

- Stack : \([x_{n+2}]\)

-

PC 31 –

"Get Busy"⇒LOAD_TOP(1 param)- Param at PC 32:

"Old Recliners"⇒ push \(x_{n+1}\)= heap["Old Recliners"] - Stack : \([x_{n+2}, x_{n+1}]\)

- Param at PC 32:

-

PC 33 –

"Written In Reverse"⇒SWAP(no params)- Swap top two stack values

- Stack : \([x_{n+1}, x_{n+2}]\)

-

PC 34 –

"half return"⇒RETURN(no params)- Return to address in RA Stack

- RA Stack :

[] - Stack : \([x_{n+1}, x_{n+2}]\) (used as inputs for next Fibonacci iteration)

- Heap : unchanged

Conclusion

Throughout the process of creating Splang, I learned a lot about the challenges and considerations that go into designing a programming language. From choosing the right attributes to represent commands, to designing the syntax and semantics of the language, I gained a deeper understanding of the complexities involved in language design. I also learned about the importance of testing and debugging, and revising my design choices based on feedback and testing results. Overall, this project was a valuable experience that allowed me to explore the world of programming languages and gain practical skills in language design and implementation.